What happens after you place a trading order with the broker?

Understand the trajectory of a stock during trading

We live in an era of instant gratification. You open an app on your smartphone, search for a company like Apple or Tesla, tap “Buy,” and within a fraction of a second, the screen flashes green. “Order Filled.” You are now a shareholder.

It feels seamless, almost like sending a text message. But that single tap sets off a lightning-fast, incredibly complex chain reaction involving supercomputers, fiber-optic cables, massive financial institutions, and strict regulatory checks.

Have you ever wondered what actually happens in that blink of an eye? Who sold you the stock? How did the money move? And do you actually own the shares the moment you click the button?

This guide peels back the curtain on the financial markets. We will walk through the fascinating journey of a trade order, from the moment it leaves your thumb to the moment it is officially settled in the vault.

The Pre-Trade Check: Safety First

Before your order even leaves your phone or computer to head to the market, it must pass a rigorous security checkpoint at your brokerage firm. This happens in microseconds.

Your broker’s internal risk management system instantly verifies three things:

-

Buying Power: Do you actually have the cash to pay for this trade? If you are buying $1,000 worth of stock, the system locks that $1,000 in your account immediately.

-

Stock Availability: If you are selling, do you actually own the shares? This prevents “naked shorting” or selling things you don’t have.

-

Compliance Rules: Is the stock halted? Is it a restricted security? Are you trying to buy a risky penny stock that requires a special disclaimer?

If any of these checks fail, your order is “Rejected” before it ever sees the light of day. If everything looks good, your broker accepts the order. Now, the real race begins.

Smart Order Routing: Finding the Best Path

Here is a secret most new investors don’t know: Your broker usually doesn’t send your order directly to the stock exchange (like the NYSE or Nasdaq).

The stock market is fragmented. A single stock can be traded on over a dozen public exchanges and dozens of alternative trading systems. To navigate this map, brokers use a technology called a Smart Order Router (SOR).

The SOR is like the GPS of the stock market. It looks at the entire landscape of liquidity to decide where to send your order to get the best possible result.

The Three Main Destinations

-

Public Exchanges: The famous places like the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE).

-

Market Makers (Wholesalers): Massive high-frequency trading firms (like Citadel Securities or Virtu) that stand ready to buy or sell stock at any time.

-

Dark Pools: Private exchanges used by institutional investors to trade large blocks of stock without alerting the public market.

For a typical retail investor, the Smart Order Router often sends the order to a Market Maker first. Why? Because Market Makers can often execute the trade slightly faster and at a slightly better price than the public exchange.

The Role of Market Makers: The “Supermarkets” of Finance

To understand how your trade gets filled so fast, you need to understand the Market Maker.

Imagine going to a supermarket to buy apples. You don’t have to wait for an apple farmer to walk into the store and agree to sell to you. The supermarket (the Market Maker) has already bought the apples and put them on the shelf, waiting for you.

In the stock market, Market Makers hold an inventory of stocks. When you send an order to buy 10 shares of Microsoft, you usually aren’t buying them from another guy named Steve in Ohio. You are buying them from a Market Maker’s inventory.

Why Do They Do This?

Market Makers profit from the Spread.

-

Bid Price: What they are willing to pay to buy stock from you (e.g., $100.00).

-

Ask Price: What they charge to sell stock to you (e.g., $100.01).

That tiny difference ($0.01) is their profit. Because they process millions of trades a day, those pennies add up to billions of dollars. In exchange for this profit, they provide Liquidity—the guarantee that you can always buy or sell instantly.

Payment for Order Flow (PFOF): Is Your Trade Really Free?

This brings us to a controversial but essential topic: Commission-Free Trading.

How can modern brokers let you trade for free? The answer lies in a practice called Payment for Order Flow (PFOF).

When your broker routes your order to a specific Market Maker, that Market Maker might pay the broker a tiny fee (fractions of a penny per share) as a “thank you” for the business.

Is This Bad for You?

Critics argue this creates a conflict of interest—is your broker routing the order to the place that pays them the most, or the place that gives you the best price?

To protect you, regulators enforce a rule called Best Execution. By law, brokers must guarantee that the price you got was as good as, or better than, the best available price on the public national exchange (NBBO). So, while your broker is making money on the backend, you are generally still getting a fair market price.

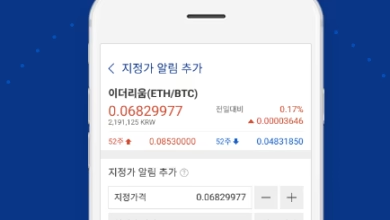

The Order Book: Where Buyers Meet Sellers

If your order is sent to a public exchange instead of a market maker, it enters the Order Book.

The Order Book is a real-time electronic list of everyone who wants to buy and everyone who wants to sell.

-

The Bid Side: A list of buyers, sorted from the highest price they are willing to pay down to the lowest.

-

The Ask Side: A list of sellers, sorted from the lowest price they are willing to accept up to the highest.

The Matching Engine

The exchange’s computer (the Matching Engine) constantly scans these lists. The moment a buyer’s price meets a seller’s price, a trade occurs.

-

Market Order: You tell the engine, “I don’t care about the price, just get me the stock NOW.” You will instantly be matched with the cheapest seller available.

-

Limit Order: You tell the engine, “I will only buy at $150 or less.” Your order sits in the book, waiting until a seller agrees to drop their price to $150.

The “Fill”: Confirmation vs. Reality

Once the match is made, your broker sends a notification to your screen: “Order Executed.”

Your account balance updates. You see the shares in your portfolio. You feel like the owner. But technically, the trade is not done yet.

At this specific moment, you have entered into a binding contract. You have promised to pay, and the seller has promised to deliver. But the money hasn’t actually moved, and the official ownership records haven’t changed. This period is known as the Clearing and Settlement phase.

It is the difference between signing the contract for a house and actually getting the keys on closing day.

The Hidden Backend: Clearing and The DTCC

Behind the shiny apps and flashing numbers lies the plumbing of the financial system. In the United States, this is dominated by an entity called the DTCC (Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation).

The Clearing House

At the end of the trading day, millions of trades have happened. It would be a logistical nightmare if every broker had to mail checks and stock certificates to every other broker.

Instead, they use a process called Netting.

-

Broker A owes Broker B $10 million for Tesla stock.

-

Broker B owes Broker A $9 million for Apple stock.

-

Instead of two transfers, the Clearing House calculates the difference: Broker A just sends $1 million to Broker B.

The Clearing House acts as the central counterparty. It effectively becomes the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer, guaranteeing that if one bank goes bust during the day, the whole system doesn’t collapse.

The Settlement Cycle: What is T+1?

For decades, the standard settlement time was “T+2” (Trade Date plus two business days). This meant if you bought stock on Monday, you didn’t officially own it (and the seller didn’t get the cash) until Wednesday.

However, as of May 2024, the US markets moved to a T+1 Settlement Cycle.

Why the Delay Exists

Why isn’t it instant? Even with computers, the system needs time to:

-

Verify the trade details between institutions.

-

Arrange the wire transfers of massive amounts of cash.

-

Update the official ledger of ownership.

During this T+1 period, your broker is essentially lending you the stock to look at in your account. The legal transfer of title happens overnight.

Cede & Co: The True Owner of All Stocks

This is the most mind-bending part of the process.

If you look at the official shareholder list of a company like Apple or Coca-Cola, you will likely not see your name. You won’t even see your broker’s name.

You will see the name “Cede & Co.”

Cede & Co. is a partner organization to the DTCC. They technically own the vast majority of all publicly traded stock in the United States. Why? Because physical paper stock certificates are a thing of the past.

Instead of moving certificates around, the system uses Book-Entry Ownership:

-

Cede & Co holds the master certificate in a vault.

-

Their books say, “Broker A owns 5 million shares.”

-

Broker A’s books say, “Customer John Smith owns 10 shares.”

You are the Beneficial Owner. You have all the rights—dividends, voting, and the right to sell—but the system tracks it via a hierarchy of ledgers rather than your name on a physical piece of paper at the company headquarters.

What Happens When You Sell?

The process works exactly in reverse.

-

Order Entry: You place a sell order.

-

Risk Check: Your broker confirms you actually have the shares in your account.

-

Routing: The order goes to a Market Maker or Exchange.

-

Execution: You are matched with a buyer.

-

Settlement: Your shares are removed from your account, and cash is credited.

The “Unsettled Funds” Rule

If you sell a stock on Monday for $5,000, that cash is technically “unsettled” until Tuesday (T+1). Most brokers will let you use that money immediately to buy another stock (in good faith), but they won’t let you withdraw it to your bank account until the settlement is complete.

If you use unsettled cash to buy a stock and then sell that new stock before the first cash settled, you trigger a Good Faith Violation. This is a common penalty for new traders who don’t understand the settlement timeline.

Anomalies: When Things Go Wrong

The system works perfectly 99.9% of the time. But sometimes, you might experience hiccups.

1. Slippage

You place a Market Order when the stock is at $100. But by the time your order travels through the internet, reaches the exchange, and gets filled, the price has jumped to $100.10. You paid more than you expected. This is called Slippage, and it happens frequently during high volatility.

2. Partial Fills

You want to buy 1,000 shares of a small, unpopular company. There might only be 500 shares for sale at your limit price. You get a “Partial Fill.” You bought 500, and the order for the remaining 500 stays open until more sellers appear.

3. Trading Halts

If a stock moves too fast (e.g., drops 10% in 5 minutes), the exchange automatically pauses trading. This is a LULD (Limit Up-Limit Down) halt. Your order will be stuck in pending status until the market reopens.

Why Understanding This Matters for You

You might ask, “Why do I need to know this plumbing? I just want to make money.”

Understanding the mechanics of a trade makes you a smarter investor:

-

Cost Awareness: You understand why Market Orders can be dangerous in volatile times (slippage).

-

Patience: You understand why you can’t withdraw your cash immediately after selling (settlement).

-

Confidence: You understand that your assets are protected by layers of segregation and regulation, even if the broker app crashes.

The next time you tap that “Buy” button, take a moment to appreciate the technological marvel that just occurred. In less time than it takes to blink, you navigated a global network of risk checks, routers, market makers, and clearing houses to secure your piece of the global economy.